HONESTY CIRCLES - AM I NOT RICH ENOUGH TO BE ETHICAL?

Up till last November, I was nowhere near being an ethical consumer. I had trained myself to what I previously thought was the pinnacle, enlightened state of shopping – a state where I could visually block out “distractions” in the form of packaging labels to efficiently filter through price tags.

That’s right. Especially for groceries, price was, for me, THE foremost concern.

I reasoned, how much difference can there be among the products? I wasn’t very particular about taste, nor quality. To me, the fact that the products were all allowed to be on sale showed that they were all certified safe for consumption/usage anyway. My lack of care was almost inconceivable to most of my friends. It was to the extent that when I was doing an exchange program in Europe, I only realized after three months that the tough but cheap “chicken” meat I was buying was actually turkey meat on sale. I hadn’t bothered looking at the label and through the transparent cling-wrap it did look a lot like chicken. Price was my first filter when it came to purchasing. Other than price, everything else was secondary.

I just bought whatever was most available, cheapest, most convenient.

I was re-introduced to this idea of ethical consumption when I started my internship stint with PlayMoolah where their latest project involves innovating on ways to connect socially responsible companies with consumers. “Ethical consumption” became the new buzz-word. I was bombarded with names of multiple ethical suppliers (Javara, Toraja Melo, Kakao, Seventh Generation, Aleppo soap etc.) - which astounded me because I never thought that the ethical consumption market was so extensive. There were options for ethical fashion, ethical food, ethical personal care products, ethical home living items. You name it, we have it.

I started hearing more about the narrative of how every single dollar we spend impacts the world we live in, especially when I started speaking to more people who identified themselves as “ethical/conscious consumers”. From these passionate groups of “ethical consumers”, I became more and more convinced that by using our purchasing decisions, we could “vote” for practices we wanted to see in an ideal world.

We often underestimate our power as individual consumers, thinking that we are just one out of many. But, imagine this, if we can influence and galvanize fellow consumers into a common desire for change, we consumers as a whole can have a sizeable impact on producers’ decisions. Given a united demand by consumers for ethical produce, producers will potentially have to remodel their business practices to align with the practices and processes that consumers desire.

We, consumers, can contribute to a better world, starting from the simple purchasing decisions we make everyday.

The power of being able to change the world, starting with a single step, was a compelling concept. I wanted to be an ethical consumer too. Like people my age, I immediately turned to google to see what ethical alternatives there were to the products I usually buy. After an initial browse, the foremost thought on my mind was...

“Wow, why are ethical goods so expensive, maybe I’m not rich enough to be ethical?”

I had started my search by first looking at ethical fashion – clothing products made by people of disadvantaged communities or products that are manufactured in ways that minimizes negative impact on the environment. What I saw were products that were around 200-500% markup to the ones I can buy at Bugis Street. Granted, some pieces looked really good and the material was quality-grade, but the prices were comparable to those of high-end brands.

The budget queen in me immediately sounded the alarm. As a student whose only source of income comes from once-in-a-year angbao money and internship allowance, I immediately concluded that ethical fashion was a luxury I couldn’t afford. For the cost of 1 ethical dresspiece, I could get myself maybe 5 different dresspieces from another store. 500% increase!

But wait a minute! At this point, I took a double take. On closer look, the problem really wasn’t that I couldn’t afford it.

On my trips down to Bugis Street, I buy 5 to 7 items on average (most of which I end up not wearing). The problem wasn’t the money, but the fact that I wanted the “best deal” for myself. It was the nagging thought that “If this amount of money can give me 5 items, why should I settle for only 1?” We want to get most out of the amount we spend, and we sometimes mindlessly prioritize quantity over deeper thoughts of the quality of the item and the production practices it supports. I wanted the variety and quantity, even though I didn’t really need it. To think about it, it isn’t actually necessary to have a different get-up every single day of the month. Also, the quality of the produce I can get from ethical fashion is also generally more durable than that of my Bugis Street steals, making me able to wear those ethical clothing over a long period of time. All of a sudden, the ethical dresspiece seems reasonably priced.

I believe there are others out there like me, who have mental benchmarks of what we consider an affordable price and beyond that, we view a product as “out of reach”. Yet, often, we go on to spend so much on similar products that it adds up to the same as, or perhaps more than, the one product we turned down because of the seemingly high price.

It is important to note as well, that there is a very good reason why ethical products are more expensive that normal products. Sometimes, the products are handmade by members of disadvantaged communities (i.e. Toraja Melo and Gift and Take) and it takes more labour hours and effort to complete each product. Or, it could be that some of its materials are made with more environmentally-friendly procedures that increase the production cost (i.e. Aleppo’s soap uses all-natural ingredients with antiseptic properties, and are handmade by Syrian refugees.)

Furthermore, the one obstacle that most ethical producers face is that they just haven’t got the scale of business to reap economies of scale. This results in a smaller consumer base, because many consumers don’t want to pay such high prices. This vicious cycle traps them in a perpetual futile struggle to reap economies. Thankfully, all is not yet lost - some of us might be able to help. For those of us with the financial ability to buy from these socially-conscious enterprises, why not step in to support these ethical products, and further the good work that they are doing?

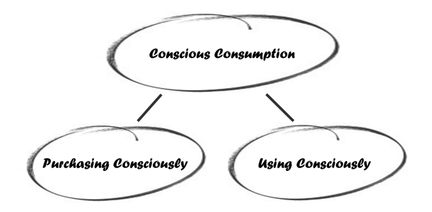

There are however, simple ways to consume consciously which we can employ, no matter our financial situations.

One way is to consciously reduce the waste we create in our consumption habits. This includes using less of disposable products (wooden chopsticks, plastic spoons, plastic bags, etc.). Another way is to participate in the sharing economy and be open to procuring products that aren’t brand-new but still usable. Examples include buying textbooks second-hand, renting items that we need for limited periods rather than buying them, etc. For more ways on reducing waste, check out this delightful article on zerowastehome.com.

The list of things we can do to practice conscious consumption is non-exhaustive, no matter our financial means. My hope is that through becoming aware of how easy and simple conscious consumption can be, we can become more willing to make small changes in our everyday lives in pursuit of a better world. As we venture forth to discover and adopt exciting innovations, be it new or old, let us rejoice in the changes we create, slowly but surely.

Sign up to our newletter

Keep up with Playmoolah's latest news and offers!

Thank you!

Who we are

PlayMoolah enables Financial Emotional Resilience® for a Flourishing Life

A Brand of The Moolah Group

A Partner Company to The Wealth Resilience Institute

A Brand of The Moolah Group

A Partner Company to The Wealth Resilience Institute

Get in touch

-

10 Anson Road, #44-12,

International Plaza,

Singapore 079903 -

info@playmoolah.com

Copyright © 2026